SuperRare Is Bringing in a New Wave of “Dank” Meme Economists

While $100,000 CryptoKitties and digital race cars have earned non-fungible tokens (NFTs) a special place in the speculator’s heart, artists and designers are getting excited about the space for much different reasons.

The crypto aesthetic, “dankness” as a metric of quality, and multi-media art experiments all paint a much more original picture. Still, and according to SuperRare founder John Crain, there is much work to be done before this niche space begins competing with the likes of Christie’s.

What Is SuperRare?

Founded in 2018 by Crain, SuperRare is an online gallery of sorts where users and artists can post and purchase original pieces of digital art. Anyone can join the platform, and to get started collecting one only needs an Ethereum wallet like MetaMask.

An artist in good faith looking to explore alternative venues is exactly the demographic SuperRare is looking to attract. That’s also part of why the process to simply purchase a work is only slightly less rigorous than joining the platform’s network of artists.

“You pretty much just need to show that you’re serious about being an artist,” said Crain in an interview with BTCManager. “There is a vetting process that we go through once a week where we look through a prospective artist’s portfolio of work to see if they’d be a good fit.”

Once an illustrator or designer has been admitted to post their art on the site, they are also immediately eligible to begin earning real digital money, specifically ether (ETH). At the time of press, no pieces of art have reached the parabolic levels of a CryptoKitty in 2017, but the concept does reveal a slightly more sustainable collector’s experience.

(Source:SuperRare)

Each time an artist submits their .gif or .jpg creation, a token is generated that remains permanently bound to the piece of art. This token is recognized by the Ethereum network, hence the necessity for an ETH-compatible crypto wallet. From there, a collector is able to buy, trade, or sell this token (and thus the digital rights) that represents the artwork. Alternatively, an artist can set a stagnant price for the piece that cannot be bid on.

Once a buyer has purchased a piece of art, a smart contract-enabled patronage mechanism ensures that the creator is compensated. When another buyer purchases the token, and thus the piece of art, the same mechanism kicks in and the creator is paid a percentage of the bid. The value chain of digital art on a platform like SuperRare is markedly different from the legacy artworld.

Typically, an artist has little say in the valuation process of their creation. They may earn a commission of the initial purchase, but as soon as the piece goes to auction, all value is re-captured by the auction house or holder of the art. A handful of different blockchain-native models are exploring the ways that the technology can include the artist in this exchange throughout the life of their art.

Simon de la Rouviere has employed a Harberger Tax in a recent art and crypto experiment. In his project, “This Artwork Is Always On Sale,” a piece of art is always on sale, meaning anyone, at any time, can purchase the art. If the holder isn’t interested in selling the piece, they simply need to set an extraordinary price for the art. This won’t guarantee that the art will ever be bought, but it creates a wholly new dynamic in the art market.

Like SuperRare, a flat five percent of any purchase of Rouviere’s piece always goes back to him no matter how many times the piece changes hands.

https://twitter.com/simondlr/status/1108842621051506690?s=20

It’s radical for sure, but by attaching a smart contract to the piece, the creator is always included in the buying and selling of the piece.

Likely, readers have already read heavily about the tokenization of artworks. Artory, MasterWorks, Maecenas, CoArt, and a host of others are all approaching the space with a similar tool. Another difference, however, is the type of community each project seeks to engender.

Aesthetics are everything and as Crain explained, “SuperRare isn’t looking to compete with Christie’s. We just want to be a compliment.”

Measuring “Dankness” and the Rise of CryptoArt

Before founding SuperRare, Crain explained how his work at ConsenSys had inspired him to further explore the NFT space. “I suspected that NFTs were going to be huge in consumer applications. They would create new business models and that’s sort of where I began tinkering,” he said.

His background in user design led him to create a tokenized version of Instagram, something similar to what Editional is doing now. Crain also described the influence of CryptoPunks and the emerging aesthetic that comes with digitally-native art. Launched roughly a year earlier, the co-founders of Larva Labs, Matt Hall and John Watkinson, laid down the groundwork for what would explode into the thriving NFT ecosystem the space is now making room for.

At that time, Hall said that “The whole thing is pretty weird, and that’s kind of why we did this. There’s like a weird intersection here between these virtual, digital things and an artificial rarity, but a rarity that is real and valuable in some sense.”

So weird was this development that it has earned the title of “CryptoArt,” a movement distinct from anything before seen. Jason Bailey of the blog Artnome wrote the seminal post on the subject declaring “art native to the blockchain has its own aesthetic and represents a new and important movement within art.”

(Source: Artnome)

Getting to the heart of this aesthetic is easier said than done, however. In their collective work, “There is no Such Thing as Blockchain Art,” members of the Ethereum community explored several delineations of the crypto and art world. In the first, and as mentioned above, the document identifies the ways in which the technology is helping reinvent the art marketplace via registries and provenance. Albeit an important improvement, the work goes on to say:

“In terms of the implementation of the technologies in art pieces, the wide majority has failed to achieve technical and conceptual consistency.”

The distinction made here falls into the much broader category of what art fundamentally is and if art made using these technologies fits into that definition. It’s complicated, but the work of the Department of Decentralization (DoD) reports that all is not lost. In fact, it may only be a question of semantics.

According to Bailey, “it is best to judge CryptoArt by ‘dankness’ or potency of expression and creativity” and “because CryptoArt is open to everyone, judging it by traditional artist standards kills what is great about it.”

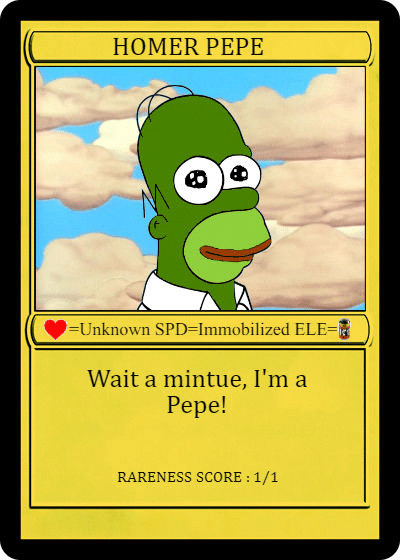

Crain added that a piece of CryptoArt is “dank” if it is capable of spreading like wildfire throughout the Internet, much like how successful memes work. Thus, it’s no surprise that adding scarcity to a meme using blockchain has also seen myriad use cases. Trading cards, collectibles, or crypto-fied .jpgs show how something as amorphous as digital virality can be captured, tokenized, and generate real-world value for its creator and collector(s).

Following these lines, the DoD’s discussion on blockchain art indeed qualifies memes as art, unlike the rest of the art world. This inclusion is yet another major difference between a place like SuperRare and Christie’s. As traditional art institutions close themselves from emerging mediums and experiments, other platforms are exploring the fringes of what art can be.

The overriding motif to this discussion is that blockchain, wherever it appears, continues to add disruption and a reexamination of first principles. This has been evidenced time and time again in the world of finance and technology.

And to include the art world in that conversation is either indicative of the technology’s true potential or of humankind’s ability to oversensationalize new ideas. Ten years of Bitcoin isn’t much compared to the rest of the tech space and only time will tell which narrative ends up being the dankest.