Web3 Summit Pt.1: Metaphorical Mental Models and The New Internet

Navigating the emerging Web3 ecosystem can seem like translating a massive marketing plan. Small startups will decentralize this, others will offer micropayments for that, and they’re all going to “right” the wrongs of the Internet. While some of this is true, the term doesn’t seem to capture the actual stack of technologies that will make up this next step.

A History Lesson on the Internet

It would be difficult to sit in the main hall of the Web3 Summit in Berlin from October 22 to 24 if one were an employee of Facebook or Google. If an employee from the FANG group did, however, make it through the front doors of Funkhaus for the three-day event, they would gain a much better understanding of their ideological opposition. They may also get fed up with the phrase, “Web3 will smash Web2’s conglomerates.” But, if they were from a particular era, such as Web1, the whole scene might not be threatening at all. It might even look like a whole lot of the same.

Fortunately, the arrival, advantages, and destructions of the Internet happened relatively quickly. Thus, few of the founders have passed away, and many of their colleagues are eagerly taking up the torch. In a bid to steer the starry-eyed dApp developers and infrastructure pipe layers, Harry Halpin of Inria and formerly a sitting professor at MIT provided the audience with a telling history of the Internet’s first iteration. He charismatically explained how much of the ideological warfare occurring between cryptocurrencies is reminiscent of the groups who fought over which standards should be standardized. He told about which hills developers were dying on and which were being given up for the sake of long-term success.

This is a serious moment for the web’s future. But I want us to remain hopeful. The problems we see today are bugs in the system. Bugs can cause damage, but bugs are created by people, and can be fixed by people. 1/9

— Tim Berners-Lee (@timberners_lee) March 22, 2018

Interestingly, this isn’t the first time Haplin has heard of decentralization either. The Internet, according to Tim Berners-Lee, was intended to be just that. He explained that a group of “hippies” in the seventies began planning what would hopefully allow the digital world to enhance the meatspace. They asked how could a technology make us more social, more connected, and more human?

For starters, an augmented social network was going to need a persistent identity. The early innovators were just as eager as the Civics of the blockchain world were to give users a common, sticky name tag that they carry around the Internet when meeting other Internauts. It wasn’t easy of course, as no one could decide on which company or service would provide that identity. Soon, in Web2, the decision was made for us.

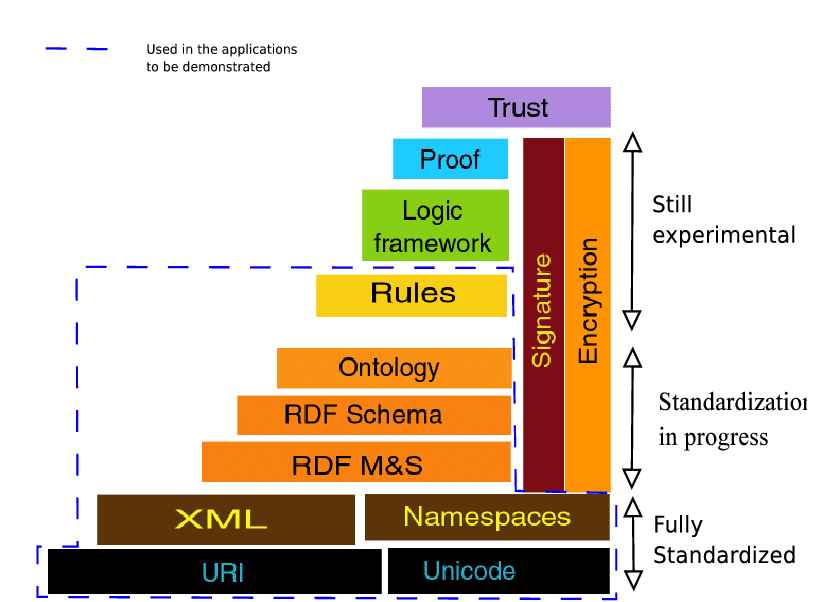

But, backing up before this slippery-slidey-give-users-clean-identities moment, to the early iterations of a decentralized web. Haplin reminded observers that Indymedia, FOAF, and Berners-Lee’s dream of “The Semantic Web” were all in the works. Unfortunately, the developers shot themselves in the foot and rolled out the red carpet for you know who. By failing to earn consensus at critical moments, nothing could be agreed upon and then built atop. It was chaos and open-source. It was decentralized and vulnerable. Soon, the world’s first shot at decentralization was bought out, wrapped up in NDA agreements, and re-released as the famous “Like” button. “It’s the greatest use case of decentralized technologies ever,” Haplin yelled to the crowd. “And Facebook has it!”

The Semantic Web Stack in full color.

(Source: W3)

So, can blockchains save us and get us back to a decentralized internet? Yes and no. The critical element of the computer scientist’s presentation was the context it provided. The swarming egos of BIPs, EIPs, soft and hard forks, all look tragically similar to the rise of the internet. Fortunately, the incentives model lines up a bit better. By buidling an Internet with a native economic structure, buidlers and entrepreneurs are less dependent on large companies to fund their projects.

On the one hand, the space sees the unfounded ICO craze, on the other, it also enjoys a degree of sovereignty not enjoyed by Haplin’s generation. Still, soft power and egos can quickly throw a wrench in the machine, no matter how optimistic it may seem.

New Browser, Same Data

The built-in economy is not lost on those hoping to relieve the world of the infamous ad-revenue model. Or worse still: paywalls. The Brave Browser is likely the most popular attempt at this. Dr. Ben Livshits, the chief scientist behind Brave, explained how the dying business plan for making money of clicks and views was slowly trickling away. Good riddance: “Imagine that you could use micropayments to read a portion of The Economist. Imagine monetizing all the likes and retweets from Twitter,” Livshits explained. The token-operated browser has convinced at least ten million users of this logic, as the dApp has seen just as many downloads.

It’s still early days for the startup, however. At current, Brave is still in the Gemini phase (browser release and beta launch), but each step leading up the final Apollo manifestation looks like the perfect advertising cleanse. Or, if you can stomach a few more pop-ups, the browser will pay users in its native Basic Attention Token (BAT). On the way to Apollo, the group is also hoping to make some friends in the form of IPFS, unmentioned decentralized identity protocols, and even more YouTubers moving over to the browser.

Quickly, a world without Chrome and other nasty ad trackers look like a thing of the past. For a final knockout blow, Ocean Protocol later laid out the Ocean substrate which opens the data machine much like Bitcoin opened the financial machine. The founder of the project Trent McConaghy described how the Token Economy inspired his work with the Ocean Protocol and the Data Economy:

“Data is money, or as valuable as oil. And as we are the ones providing that data, we’re also bearing witness to the greatest arbitrage of humans in history.”

The data collected on users is bought and sold to the highest bidder for the highest price. More importantly, this data is slowly, but evermore precisely being cornered and snapped up by Facebook and Google. Thinking in terms of these data silos like hodlers think of Wall Street in 2008, paints a clear metaphor for what’s at stake.

In Web3, Networks Are Companies

The final group of panelists continued the metaphoric journey when describing how investors should be participating in decentralized projects. Engaging in the conversation was Olaf Carlson-Wee of Polychain Capital, Richard Muirhead of Fabric Ventures, Shuoji Zhou of FBG Capital, and Jutta Steiner of Parity Technologies moderated.

One of the greatest strengths of this emerging technology is the power of the metaphors it employs. Few subjects are left unscathed and a majority of the time, the non-technical part of the room is deeply thankful. To better grasp how these three figures are thinking of investing, Carlson-Wee astutely described networks as companies: “Investors must participate in on-chain governance. Not doing so, is like a large shareholder of Apple not showing up at the shareholders meeting.” It should also be noted that Polychain Capital also controls the largest node in Tezos.

Muirhead followed this up with the declaration that “it’s no longer the boardroom. It’s the blog post,” while Zhou explained a bit more behind the philosophy of treasures when it comes to cryptocurrencies rather than shares in a company. The final test of this new investor-project relationship is determining the fiduciary role the former takes while also considering the practical needs of the latter.

It all gets a bit blurry regarding who’s helping who in the end. And, likely, that’s the point; in decentralizing all the things, Web2 didn’t go far enough. Or, perhaps we just haven’t found the right metaphor for the new monsters on the horizon.